Natural Dye Experiments

Working with wool is a tradition spanning many centuries in the Outer Hebrides. Wool was essential for clothing and also as a source of income – the production of “quhyte plaiding” constituted a form of rent payment in the sixteenth century. By the mid-twentieth century Harris Tweed, the unique wool cloth made in the Isles of Lewis and Harris, was of global renown and became the largest cottage industry in the world.

Traditionally, women dyed the fleece and spun the yarn for knitting and weaving whilst the hand weaving was generally undertaken by the men. By the early twentieth century the industry had grown to such an extent that mills were built for all the processes involved in making yarn for the hand weavers. Synthetic dyes became readily available and had compelling advantages over natural dyes: ease and speed of production; a much wider variety of colours; colour fastness and uniformity of result. It would also have been unsustainable to use lichens and plants on a such a large commercial scale. This inevitably meant that the art of natural dyeing shrank away within a generation.

I was lucky enough to grow up at a time when there was still a good deal of knowledge about the use of natural dyestuffs; my grandmother’s generation had been steeped in the art. As well as a general shared knowledge of suitable plants and lichens to gather, which substances to use and how to brew, each dyer developed her own special recipes which she guarded jealously. Some women were known to have gone to their graves without divulging their recipes. Colour was one of the few ways to express a distinctive and unique appearance among people who possessed very little, and so it is understandable that they wanted to have something to wear that allowed them to stand out from the uniform hodden grey that was the cursed colour of the peasantry through out the land .

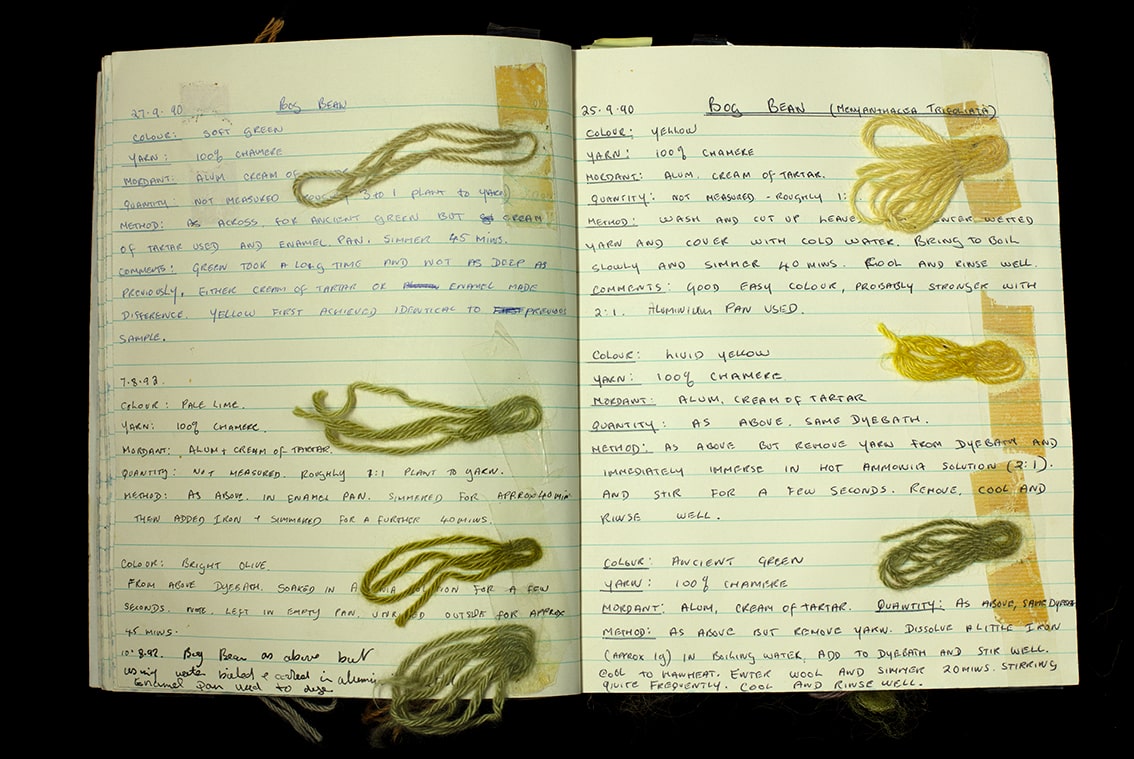

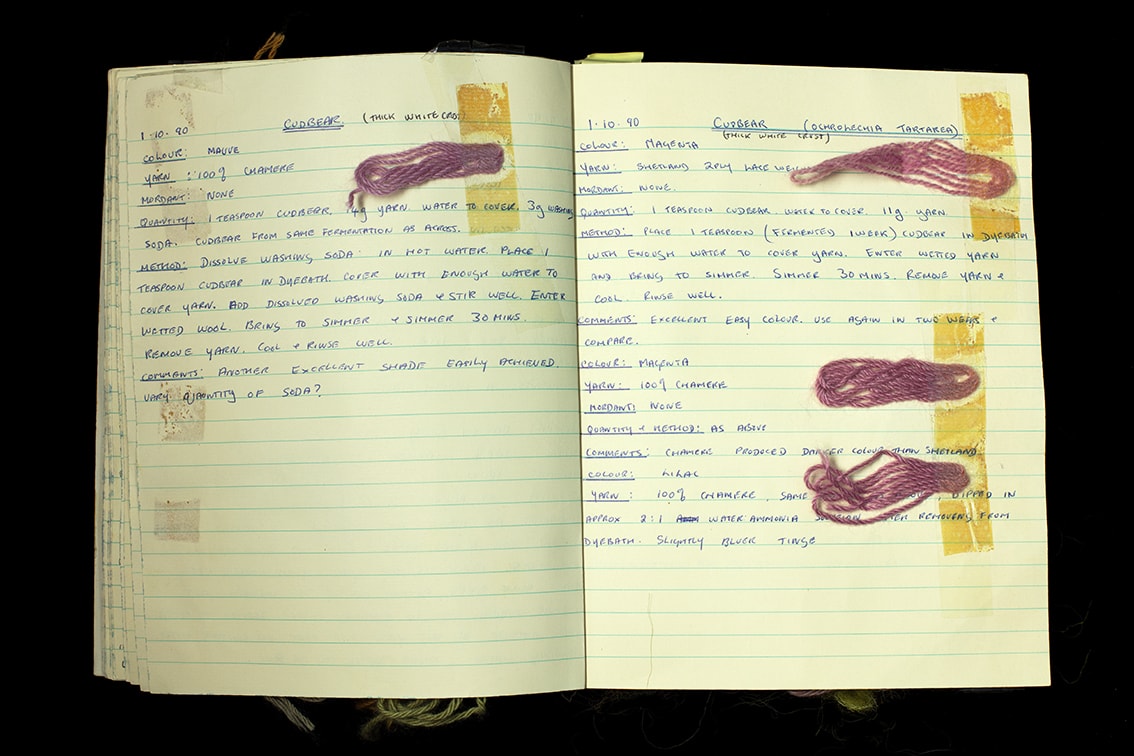

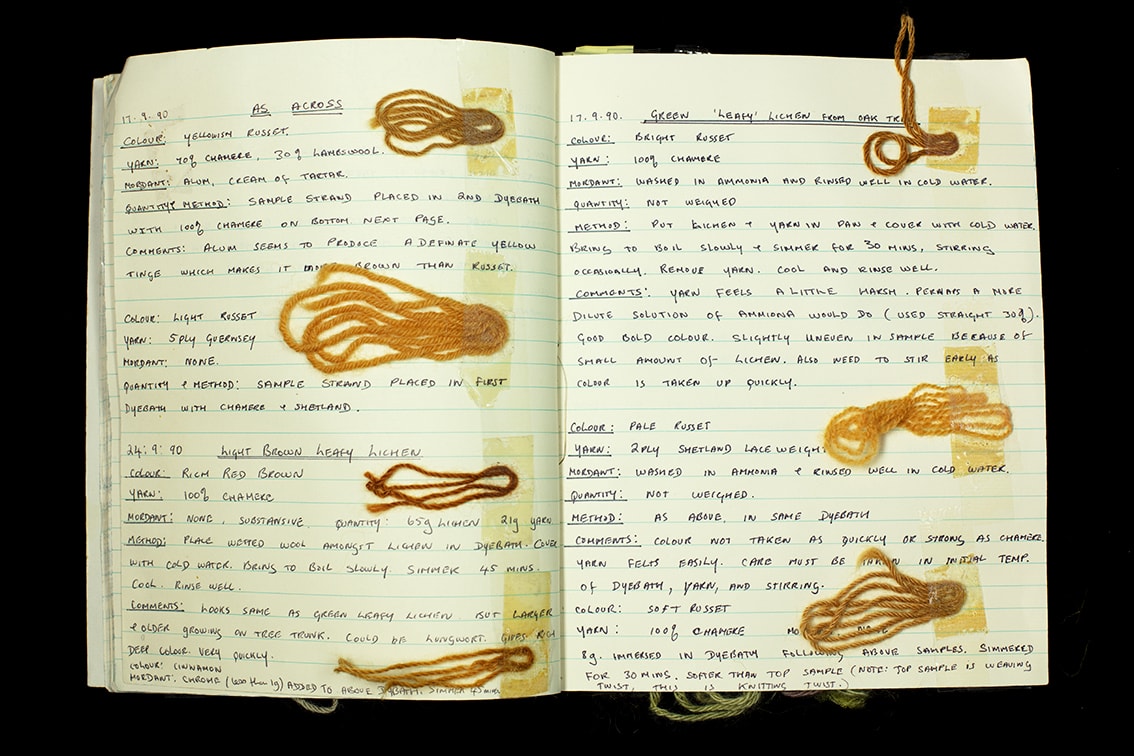

My approach has always been a combination of this knowledge passed down, together with scientific experiment. There is always a great feeling of having achieved something uniquely magical when an idea comes to life in a new shade, and so I can relate to the dyers of the past and their desire to keep their special colours for themselves.

I experiment with small quantities and focus on developing my understanding of the effects that can be achieved through a wide spectrum of variations. This entails recording each process in detail, including where and when I gathered the material and what the conditions were like when I did so. I can then compare the different results of the same material gathered from different places and in different conditions.

The results are often surprising and always inspiring and I have used them to inform many of the shades that permeate my yarn range.